W. Eugene Smith at 4th floor window of 821 Sixth Avenue (ca. 1957).

W. Eugene Smith at 4th floor window of 821 Sixth Avenue (ca. 1957).(W. Eugene Smith © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith)

By far the most exciting bit of photographic detritus that has lately washed up on our cultural shores is the Jazz Loft Project:

"From 1957 to 1965 legendary photographer W. Eugene Smith made approximately 4,000 hours of recordings on 1,741 reel-to-reel tapes and nearly 40,000 photographs in a loft building in Manhattan's wholesale flower district where major jazz musicians of the day gathered and played their music. Smith's work has remained in archives until now. The Jazz Loft Project is dedicated to uncovering the stories behind this legendary moment in American cultural history."

From these archives, a ten-part radio show has been compiled by Sarah Fishko for NPR. The seventh episode played today on "Weekend Edition." Check your local listings for the last parts. The introduction and the first seven episodes can be found here. Needless to say, there are all sorts of extra visual and aural bits and pieces from the project that can be seen there on the website as well.

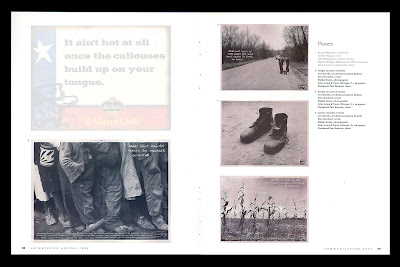

In addition, in conjunction with the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, Knopf is releasing a book of photographs by Smith with snippets of transcribed audio. The Jazz Loft Project: Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue, 1957-1965 by Sam Stephenson is just fantastic and a hell of a lot of fun. The book features Smith photos of the jam sessions that seemed to be going on virtually every night through morning (it was considered rude to show up before 11 pm.) It seems that just about anyone connected with the jazz world in the late '50s showed up and Smith incessantly photographed them all and the environment around them.

(Left) Thelonious Monk and his Town Hall band in rehearsal, February 1959.

(Left) Thelonious Monk and his Town Hall band in rehearsal, February 1959.(Right) Zoot Sims (ca. 1957-1964).

(W. Eugene Smith © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith)

Further, Smith seemed to have photographed everything that passed by his window as well. Half the photos in the book are ones shot from his window on the fourth floor--life drifting by, caught and pinned to the tarmac backdrop by Smith's telephoto lens.

(W. Eugene Smith © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith)

Not his best work certainly, but add to the mix reproductions of the reel-to-reel boxes of every imaginable manufacture covered with Smith's notes and indexing (one reel labeled: Hard, Grim. A dope tape, stereo), pawn shop tickets, letters and album covers as well as reminiscences by people who passed through and you start to get a remarkably detailed document of a thin slice of American life and culture at a very specific time.

And then, there are the tapes. They include legendary musicians talking shop; Smith discussing photography; Smith and other residents arguing living conditions; contemporary radio shows and tv mulling the concerns of the day; music live and recorded music re-recorded; junkies, hop-heads, dealers, thieves, drunks or walk-ons from the street talking shit; and, apparently, hours of nothing but the building breathing. The transcribed conversations provide a microscopic view of a fascinating subcultural community during a period of creative upheaval.

"Christmas Eve, 1959

Zoot Sims [saxophone] , pianist Mose Allison, saxophonist Pepper Adams, bassist Bill Crow, and others in the loft:

'Come on, Mose, one more tune, just one more.'

'I have to make it home. It's Christmas Eve.'

'It's actually Christmas Day now.'

'We won't have a piano player if you leave.'

'One more, come on, just one more.'"

These are the tiny shards of life that usually end up in the trash bin of history--shards that when assembled can transport you into another time and place with such vivid resonance that you could fool yourself into thinking that all these are your own memories.